When my kids ask me where I was when the coronavirus pandemic of 2020 hit the world, I’ll tell them I was on the shores of the Indian Ocean in Bagamoyo, Tanzania.

En route to the airport on Monday, March 16, a humid evening as crows circled the sky above our safari truck ride, young men shouted “corona corona” from the streets.

The traffic cops in white with orange glow sticks let out laughing sneers as they waved us by. An older woman selling passion fruit pummelled her hands at the air with frustration saying something in Swahili. Haraka haraka. There was no mistaking her feelings or the others who stared at our group of mostly Canadian students, so different from the friendly and smiling faces from earlier that week. She wanted us to leave.

Mukhtar, our Indian Kenyan local transportation and food logistics honcho said, “They think the disease came from you white people. Imagine if you’d gone to Zanzibar, this is what people would’ve been saying to you on the street. It would not have been nice.”

“They’re not wrong,” said a student. And a silence fell on the bus.

Six months later, I’m still left processing the unprecedented times unleashed by March 2020. International travel has come to a standstill and the future of tourism remains a question mark. As someone who is able to and chooses to see the world, travel is an integral part of my identity. Without it, who am I? And how do I refigure how I participate in the world?

***

A childhood dream

From a young age – before I knew there was something called a world, and that I inhabited it – I knew I wanted to see places and help people.

Growing up, I watched Frontline documentaries on PBS and read Nicholas Kristof’s column in the New York Times. I studied International Development Studies and Economics at university (like Baby from Dirty Dancing). I took opportunities to intern at nonprofits in the Himalayas and at the United Nations. This path organically led me to Africa.

In an introductory Swahili class, my Kenyan teacher asked us why we wanted to learn the language. I answered, “I’m going to East Africa for study abroad. And maybe I’ll volunteer afterwards.” (I cringe when I think back to this – well-intentioned but so, so ignorant.)

Thankfully, I did go on that study abroad program in 2018, and not only did I begin to decolonise my notions of Africa, it was also the most joyful time of my undergraduate years.

A semester-long program in Eastern Africa, we travelled through Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania taking field courses taught by North American and African professors in geography, anthropology, biology, and more.

Class ranged from ethnographic research in rural communities to observing red colobus monkeys in the rainforest. We celebrated a birthday under the starry skies of the Maasai Mara and had deep conversations over bonfires and beers. It was as wonderful as it sounds.

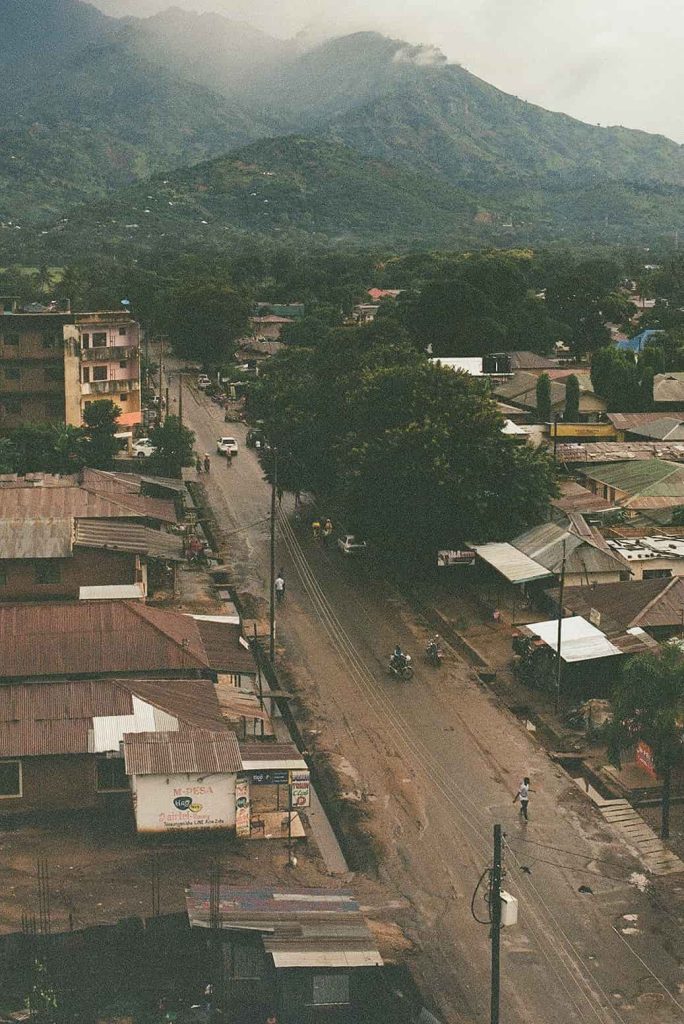

The experience instilled a love for Africa’s landscapes – the thorny acacias on the water-brushed Kenyan plains to the misty Lushoto Mountains in Tanzania. It showed me that Africa was not simply a monolith “where conditions are worst” but full of beauty and complexity as all places in the world.

I took in several positive images of the continent, all of what was missing from the newspapers and television I consumed. But more than love for a place, the unique study abroad experience inspired an affinity for the road.

Inspired by the unique study abroad experience, I launched a life abroad after graduating university. I returned to the continent for a post-graduate fellowship in Johannesburg and found myself working in the media industry in Mumbai.

In the last three years, I’ve been to fifteen countries. Beyond the childhood impetus of helping others, which now felt embroiled in moral quandaries, seeing places off the beaten path and taking notes retained its meaning.

So much so that when the opportunity arose to take part in the study abroad program that changed it all and return to Eastern Africa, this time as staff, I heard the road calling and said yes. I dusted off my big red 45L backpack from Costco, the same one I’d taken roughly two years ago, and got on a plane.

Returning to Eastern Africa during the pandemic

We arrived at Jomo Kenyatta International Airport on January 12 to Christmas decorations adorning the exit, a warm welcome from our local team, and a monsoon downpour (the rains were a good indication of what was to come).

The voyagers included: thirty undergraduate students, professors, a risk and logistics coordinator, a doctor, our Kenyan logistics team, and myself. We shuttled back to our hotel, still mostly strangers, ate samosas or samoosas as they say locally, and took a long night’s rest from jet lag.

As the student affairs and welfare coordinator, I was the primary communicator of the day’s schedule, academic advisor and support person for the students. The work was hectic but felt natural, and the students were amazing. The next few weeks saw us taking class by a hippo pool in the Maasai Mara, speaking to women of the Lake Nabugabo region about their livelihoods, and playing soccer with kids in Arusha.

Our itinerary planned to take us from Nairobi National Park to the beaches of Zanzibar by the end of March. Of course, it didn’t go exactly to plan.

There were early murmurs. We met a researcher from Tsinghua University staying in an empty hotel for Chinese roadworkers off the highway in the Maasai Mara who said all his funding had dried up.

One of my students, in tears late January, told me her parents were under lockdown in Beijing and stressed about her travelling. Without grasping the gravity of the situation, I reassured her with the fact that for now she was safer where there were no cases and resolutely forgot about it – there were too many pressing issues to think about.

Then in early March, things began to unravel. The news reports, which had previously presented it as a niche story, sounded more anxious. Then on March 12, Tom Hanks and Rita Wilson are reported to have the coronavirus. And I knew once Forrest Gump has it, this is getting serious.

Any misnomers I had that this might not affect our band of Canadian university students was shattered the next day, when news came in that Sophie Trudeau has it too. In a sudden span of 24 hours, a distant possibility had become reality. We were going home.

At this point, we were in Bagamoyo, an old town on Tanzania’s Swahili coast with miles of Indian Ocean shore and Omani-German colonial influences. At dawn, the fishermen collected their findings against an orange sky. The water was warm, the sand soft against your feet, palm trees framing your view as you looked up.

On our last night together, the students held a prom night, a semblance of normal under the abrupt circumstances, dancing and illegal night skinny dipping at the brink of a world rupture. It felt like we were leaving paradise for a dangerous reality.

Over the next few days, we departed in groups for Paris, Montreal, Vancouver, and Los Angeles. The three-hour road journey was quiet beyond the shouts of ‘corona corona’ from the streets. The airport was full of other foreigners wearing N95s and squeezing tiny bottles of scented sanitiser into clammy hands.

Before landing, the captain of my fully-seated Swiss Airlines flight transiting through Zurich said, “On behalf of the whole crew, I wish you the best for the ahead, not so easy times.” A German gentleman seated to my left reacted with uncharacteristic emotion and said, to no one in particular, “I’m so ready to be going home.” I felt more conflicted.

Navigating a world without travel

It’s been a difficult last few months in quarantine.

After days of adventure and a dramatic departure, it felt abnormal to adjust to the monotony and anxiety of the early days of the pandemic. I constantly worried about my friends in tourism in Eastern Africa whose work had come to a standstill.

I felt trapped by unrealised plans – Zanzibar, a long-planned family vacation, a job offer contingent on moving to a new country. Despite being grateful for my relatively sound circumstances, I couldn’t stop myself from ruminating ‘what could have been’ over several crisis-of-soul nights sobbing into pints of pistachio Haagen-Dazs. I got over it.

The moments I was pining for were conjured under a paradigm of possibilities that was rendered untenable with the reality of COVID-19. Life as we knew it is changed forever. But just because travel isn’t an option, that didn’t mean the things I most loved from it – exploring cultures, talking to people from different walks of life, nature – were gone too.

As I slowly began to accept the new normal, my days began to find a new rhythm of living in place. I bought succulents, read more books, and tried to find joy in smaller expanses. I found I can still be curious and learn within four walls. I used the newfound time to reflect and process my adventures, and to circumvent any despair on the death of travel.

Travel has been around since Odysseus and Ibn Batutta and Nellie Bly, it will find a way to exist in new paradigms. So while I still have nights of tears and Haagen-Dazs (the weird times keep rolling after all), they’re with greater equanimity.

Who am I without travel? It’s the wrong question. I am who I am because of the experiences travel has given me.